Tolkien's anarchism on inauguration day

"Meaning abolition of control, not whiskered men with bombs"

January 20th looms large in the fears of most of my friends and family. (But I'd I've posted this no matter who won, whichever party or pronoun.) The woman who birthed me into this vale of tears accused me of voting for the wrong candidate. This, she averred, triggered—although I came down with food poisoning six weeks before Election Day—my severe scare, the first I’d had which roused fears of my impending mortality, in what’s been, ten months and counting, a terrible expanse of barren pain.

I’d been meaning to post on J.R.R. Tolkien for a few weeks. One of my sharp-witted bookish allies, remembering my forty-two-or-three-year-ago seminar presentation at our Claremont then-Graduate School (now University, which I like less as a bespoke title) and term project on the don’s theory of '“eucatastrophe” (which must be now common enough for the spellcheck not to flag it, encouragingly), that is, the myth with a happy ending, the Christian incarnation as the faerie tale come true, at last.

I’ll expand in a future post my thoughts as to Tolkien, whose impact going on half a century ago I wouldn’t have expected, speaking of tall tales told, to have produced his own industry among the C.S. Lewis-Inklings spots spreading from evangelical campuses into the mainstream, traditionally at least (the other once-mighty flowing mainstream, the currently ebbing tributaries of the long-dominant, respectable, bien-pensant, au courant Establishment in Episcopal-UCC-Presbyterian-Lutheran Reinhold Niebuhr or Harvey Cox rather than Elmer Gantry or Billy Graham’s America, among which many confreres, soreres, and those rejecting gender binaries in the Franciscan ecumenical—soon interfaith but probably renamed “inclusive”?—community I’m affiliated with ally)…well, I’d never have imagined that the confluence of speculative fiction fans and believers longing for a certainty that acknowledges sin, encourages repentance, and accepts that faith is not no more would so grow. Irreducible to what Bishop Robert Barron, my post-Vatican II contemporary, defines pithily as “beige Catholicism” of the Seventies, felt banners, balloons, “Jesus is love” vs. hidebound tyranny of confessionals, mean nuns, Baltimore Catechism, and occluded Latin Mass.

Tolkien, in fact, was one whose last decade found himself bereft at the loss of these devotions, not alone as my parents, many of those among whom I was raised, also had to “get with the program” in self-help speak, as they had nowhere else to go as shelter. As from the storms of the counterculture. Which haven’t comforted the heirs of those, like me, reared as our teacher-Sisters doffed habits, flying nuns off to pick sugarcane in the paradise of Castro (I am not joking); their feted—Corita Kent in particular—Immaculate Heart order, once open to the ministrations of Carl Rogers’ transpersonal therapy, decamped dissatisfied en masse from two of my parochial schools in a row ca. 1968. The songbook of St. Louis Jesuits, the guitar folk singalongs of (seeing Dylan’s having a pop-culture moment this week for the umpteenth time) “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Bridge Over Troubled Water.” Where I was an altar boy, it spun its bare sanctuary around, banished statues, quenched candles, and made my mom weep when tarps were taken off. A 1971 remodel unveiled what she burst out at seeing as “it looks like a Protestant church.” This entry already threatens to veer from “our” moment…so.

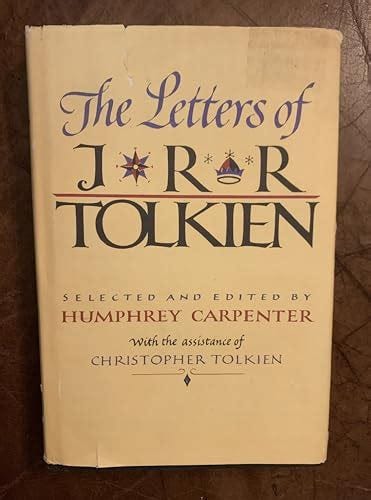

Let me pivot to this. For some reason I stumbled from a reading of Ian Frazier’s “Travels in Siberia” to a reminder of Mikhail Bakunin, which then led me to curiosity about his odd life even by nineteenth-century anarchist quirks against conformity. And somehow via Goodreads into this, which I’d long ago noted in my original ed. of Tolkien’s letters, which I understand since my cherished yellow-jacketed hardcover (discounted at Crown Books, dating it to my thrifty as always Eighties of Claremont) has been updated. Addressing his son Christopher, our pipe-smoker fumed (?) in ‘43:

My political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning the abolition of control not whiskered men with bombs)—or to ‘unconstitutional’ Monarchy. I would arrest anybody who uses the word State (in any sense other than the inanimate real of England and its inhabitants, a thing that has neither power, rights nor mind); and after a chance of recantation, execute them if they remained obstinate! If we could go back to personal names, it would do a lot of good. Government is an abstract noun meaning the art and process of governing and it should be an offence to write it with a capital G or so to refer to people. . . .

…the proper study of Man is anything but Man; and the most improper job of any man, even saints (who at any rate were at least unwilling to take it on), is bossing other men…

Not one in a million is fit for it, and least of all those who seek the opportunity. At least it is done only to a small group of men who know who their master is. The mediaevals were only too right in taking nolo episcopari as the best reason a man could give to others for making him a bishop. Grant me a king whose chief interest in life is stamps, railways, or race-horses; and who has the power to sack his Vizier (or whatever you dare call him) if he does not like the cut of his trousers. And so on down the line. But, of course, the fatal weakness of all that—after all only the fatal weakness of all good natural things in a bad corrupt unnatural world—is that it works and has only worked when all the world is messing along in the same good old inefficient human way. . . . There is only one bright spot and that is the growing habit of disgruntled men of dynamiting factories and power-stations; I hope that, encouraged now as ‘patriotism’, may remain a habit! But it won’t do any good, if it is not universal

The formidable David Bentley Hart, an impressively educated if intensively erudite Orthodox convert who tends to wax full-moon poetic in whatever fictional or factual format he assumes for his exegeses, expounded in an essay half-a-dozen years ago:

There are those whose political visions hover tantalizingly near on the horizon, like inviting mirages, and who are as likely as not to get the whole caravan killed by trying to lead it off to one or another of those nonexistent oases. And then there are those whose political dreams are only cooling clouds, easing the journey with the meager shade of a gently ironic critique, but always hanging high up in the air, forever out of reach.