Jesuitical Joyce jottings

I open two links, I find two twinned thoughts, I add a encounter for a third kind. I am the egghead. I'm not the walrus.

Last summer, despite my ineradicable agnostic leanings and because of my inculcated idealistic yearnings, I took an online version of the Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius of Loyola. Boston College provided it free, although I had to buy the spiral-bound (hadn’t seen that style for quite a while) workbook that cost me fifty bucks. However, as I annotated that with sheaves of scrap leftover copy paper scribbled full of my musings (I was brought up never to write in books, so I either have notes tucked inside, or, in a workbook to be used more than once, an alternate stack of secondhand sheets) three months of introspection (added to, well, the rest of my quotidian existence in this default mode), it worked out in guiding Doubting Thomas me in a process of discernment that, after four years stuck in a bureaucratic morass and a canonical rut, revealed a detour. I will leave that trajectory, still in very slow motion, perhaps for another entry. But, as I was searching for a decent Substack topic, this’ll fit fittingly.

Let’s just say I’ve often characterized myself as a Jesuit brain in a Franciscan spirit. With a transplant of Joycean complexity, a Pelagian outlook, and INTJ hard-wiring. Above, Ignatius pens what would become the Exercises, while on retreat in a cave in Manresa. You can find out about this Latin lover-and-a-fighter turned penitent here. While the conversion tale of the Little Poor Man from Assisi has inevitably gained legendary status for a millennium, that of Ignatius has been too often caricatured. Both figures conjure up powerful (if misleading?) archetypes for (non-)believers.

There is practically no clear, graphic image online of the two communities as one. Check out any Catholic gift shop and compare the amount of Francis-birdbath kitsch with any depiction of Ignatius as other than Alan Rickman=Sevarus Snope. By the way, my take “Beyond the Beard and the Birdbath” on medievalist Andre Vauchez’s biography, reveals the gap between pop-perceptions and non-deceptions.

But nobody dare gainsay Giotto’s delicate St Francis Preaching to the Birds (ca. 1300)

Reading the contents of my inbox (as a new colleague put it on a Whats App exchange: AOL lol) this morning, a bit of click-linking led me to this relevant essay by Peter Stockland: James Joyce ushers us into the holy. As happens now and then, it’s a serendipitous find. I’m going to quote chunks of it, as Stockland bests my acumen.

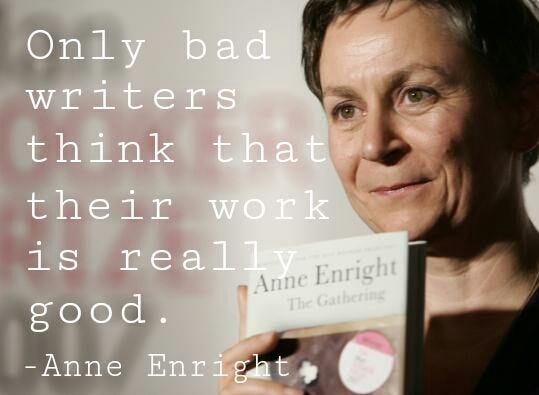

{Anne} Enright, who wrote the introduction to the Vintage {arguably now “standard” Gabler 1986, 2022 reprint} edition of Ulysses, contends it’s impossible for writers, or even the literarily aware, to be in Dublin without caring for Joyce.

“Irish writers are often asked (if) they think of Joyce, Wilde and Yeats when they walk the streets of Dublin,” Enright says. “Yes, of course we do. I think of Joyce when I walk the dog past the Martello Tower, now the Joyce Museum, where that first episode of Ulysses is set… (When) I pass Sandymount Strand on the train into town… I might think of Joyce and Nora, but more often about Stephen’s encounter with the tide. I might also briefly consider eternity….”

In a wry aside, she ups the Joyce stakes from homage to experiential. She suggests, perhaps tongue teasingly in cheek, walking across the Sandymount sand with eyes closed as Stephen does prior to his epiphany of the world’s indifference to his perception of it: “See now. There all the time without you: and ever shall be, world without end.”

I insert Enright’s Guardian 2020 reflections on the transgressive nature of the [once} notorious novel. The Irish nun who taught twelfth-grade English Lit recalled to us how she had to smuggle in a plain-brown wrapped copy from Britain less than a decade before. Stockman continues, drawing a parallel between Joyce and Seamus Heaney, who (I never knew this) lived for awhile near the Strand. He notes how…

both writers shared the fate of being devout Catholics who put aside the Catholic part but could never entirely escape the devotion.

Joyce’s pithy summary of the dilemma was telling a friend: “You allude to me as a Catholic. For the sake of precision and to get the correct contour on me, you ought to allude to me as a Jesuit.” Even for a mirror-reflecting-mirror ironist like Joyce, it seems an impossibly inscrutable remark. If Jesuits are a host species, isn’t the Kingdom itself Catholic? So where, pray tell, does the Jesuit end and the Catholic resume? Or vice-versa.

Yet in the long ago essay “Joyce, the Church and the Romantic Imagination,” George Watson argued it was the “servile timidity” and “genteel orthodoxy” of the Irish Church, not actual Catholic theology, that drove him away.

“Despite this,” Watson adds, “there is surprisingly little mockery of matters of faith and doctrine, of the actual teachings of the Church, in Joyce’s writing. The great blasphemer of Ulysses is Buck Mulligan, he of the ‘Ballad of Joking Jesus’ (who) is seen in a deeply unsympathetic light.” By contrast, Stephen Dedalus is presented sympathetically in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and “wants to be a priest of the eternal imagination, transmuting the daily bread of experience into the radiant body of ever-living life.”

Like many Irish people before and after him, Joyce was virulently anticlerical — and devoutly anti-Jansenist — but “retained respect for the central theological positions of the Church,” Watson says.

Stockland says:

I walk across the sand of Sandymount Strand with my eyes closed to offer up the prospect that Joyce, educated by Jesuits from age six to 20, can be seen not just as the contour of a Jesuit but as a writer in whom Ignatian spirituality was deeply fused à la Seamus Heaney’s talk of the relationship between imaginative processes and religious formation.

It’s not to argue Joyce was overtly practising, much less actively promulgating, Ignatian spirituality in his work. But there is a relational underlay in the experiential nature of his literature and the approach of the Society of Jesus to encountering text as world. A foundation of Ignatian spirituality is an approach to lectio divina in which the reader is directed not just to read or meditate upon a Biblical/Gospel text for inspiration, comfort or meaning, but to enter imaginatively into the passage so that he or she becomes an active participant in the moment on the page. It’s a religious predecessor to the Metaverse Mark Zuckerberg thinks he’s invented and might someday learn was the brainchild of a hot-tempered Spanish {hey—he’s Basque—there’s a definite distinction} soldier saint 474 years ago.

In Ulysses we experience what begins as literary “scene” becoming participation in Leopold Bloom’s consciousness so thorough that it transmutes into imaginatively active experience, not just textual rendering, of what we/Bloom are witnessing. Joyce, in his fiction, makes it possible for us to “enter into” life as the Ignatian spiritual exercises open us to vividly being fully present at Biblical/Gospel events.

One of my favourite examples is Bloom at Paddy Dignam’s funeral where Joyce sticks the landing of a kind of spiritual double back flip that leaves us behind the eyes and within the sensibility, and then makes us the eyes and the sensibility, of a Dublin Jew perceiving, with the intuitive understanding of the assimilated, both the substantive mysteries and surface oddity of Catholic liturgy.

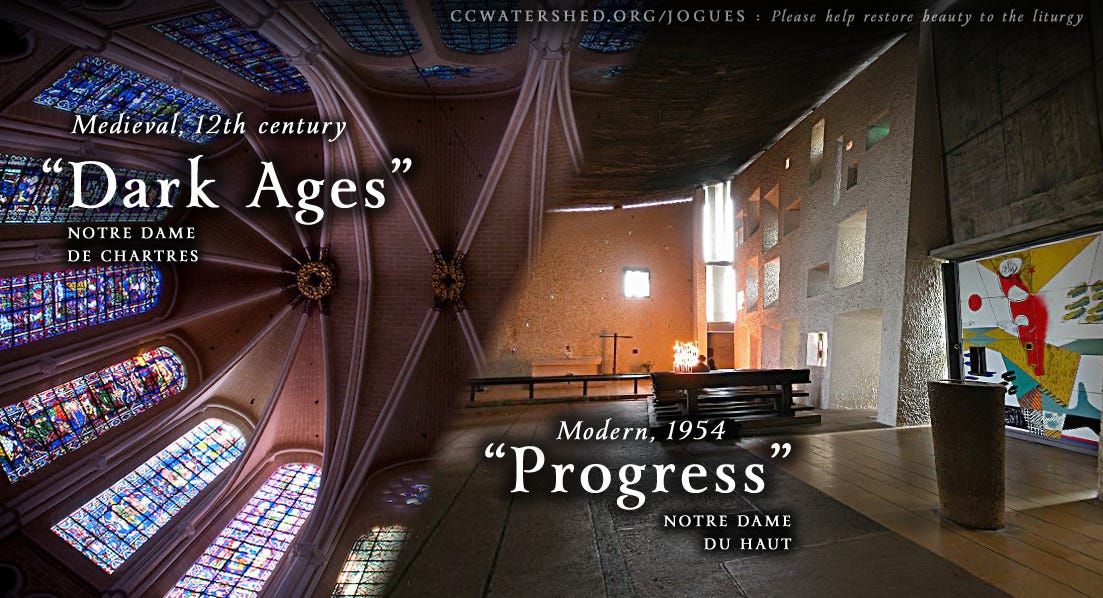

{N.B. I spent a ridiculous amount of time trying to resurrect this memorable meme. In truth, I think one could make “spirited arguments” for either camp. I’d used it a ways back in teaching art history, although I doubt if any one got it or cared. (Both that course and Comparative Religions were axed by bean-counting MBA’s.) Typical of my “student-centered” Freireian classrooms? Nobody gets my dry sense of humor either.}

He concludes, in this piece adapted from last year’s Montreal Bloomsday celebration:

Joyce did turn his back on at least the Jansenist Irish Catholic Church. But I think as we read his fiction, we can enter into at least the probability that his 14 years with the Jesuits contributed significantly to letting his literature, however irascible, however bawdy for its times, take us home as human beings, that is usher us to the threshold of the holy.

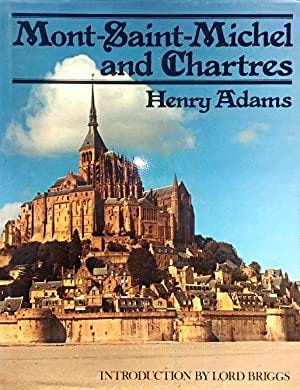

This is the edition, wonderfully illustrated, which my mom had to drive me to Pickwick Books on Hollywood Blvd. over forty years ago to purchase, for an outrageous $19.95. We both blanched at this. The clerk said that of course, I could return it in a week or two if I no longer needed it. I kept it. Reading it in the woebegone, tumbled tables, crushed couch, never-frequented, wreck of a common lounge, 3rd floor, cinderblock Rosecrans dorm, Loyola Marymount University, for my Medieval History of Ideas course. Which set me on a life’s course if not a career.

“Vatican II opened up the Church…and the people left.” Patrick Chappatte, 2012.

Next, my inbox led to Julien Kwasniewski, a traditionalist Catholic critic, son of one of the same profession named Peter, at OnePeterFive. In From Architecture to Contraception: A Journey to Paris, amidst a look at French ecclesiastical aesthetics that might have either shocked or soothed Henry Adams of Mont-St.-Michel and Chartres fame (at least for me from an undergrad Honors seminar not long before the, well I can’t call ‘em crusading, forces of DEl laid siege to my Jesuit-sponsored, for few were left to staff, alma mater), the sharp scion opines:

It is ironic that a journey to Paris, the fertile bosom of Europe’s eldest daughter, should have led to such a contracepted space. It was not a pure space but a sterile space. It had taken the heart of a venerable church and bleached it, placing the Seed that fell to the ground for the life of the world in a laboratory-like locker.

Looking back on his conversion to Catholicism in 1960, the philosopher and author John Senior wrote: “To my astonishment, as I mounted up the gangplank to the Ark, I was all but trampled by a hoard of crazy Catholics rushing to embrace in the name of ‘Renewal’ the very horror I was leaving” (from “The Last Epistle,” in the posthumously published Senior anthology The Remnants). And he added: “The Irish keep the cottages and crosses at the crossroads for the tourist trade but sing catchy liturgies in plastic Gothic chapels as they practice divorce, contraception and abortion like the rest of ruined Christendom. The body is beautiful still; the mind is best described by Joyce.”

'Modern Irish Mass missing reverence, intimacy, and parishioners' (Dublin 2018). Note how the choir outnumbers the congregants inside sterile St Philomena’s.

Stockland began his article with a nod to the Irish Catholic journalist John Waters (no, not who you’re thinking from Baltimore). I had reviewed his thoughtful take on post-Catholic Ireland in OnePeterFive myself back in 2019. Bring Back the Bad Roads tracks the precipitous path that his native land’s majority have taken, the road now travelled. Downhill, but not terminating in a delightful destination. But one where the “plastic Gothic” chapels (in Ireland’s customary usage, these are Catholic; churches are conventionally Protestant) empty except for a few grey-hairs and hollow out. For more on this, another self-promotion recommends my look at Derek Scally’s 2022 scrutiny of the Church (conventionally, the Power-That-Be’d for nearly all of the island’s history post-Patrick) in our confused half-century after Vatican II, The Best Catholics in the World: the Irish, the Church, and the End of a Special Relationship.

Not sure where, but this could stand in for most parishes in the “developed world”

Like Joyce, Heaney, Enright, Waters, and Scally, I count myself among those who struggle with a special relationship, too. An hour ago, my wife and I hosted one of her ESL students, an indigenous woman who’s been far more well-travelled than either of us, and who’s pursuing a doctorate in sociology about those who speak Kichwa. Attentive readers of my humble blog know that this remains a particular interest of mine as it parallels or diverges from the predicament of Gaeilge in a mono-lingually dominant nation. English there, Spanish here. The native tongues both endangered.

From Enright’s NYRB feature on JJ. January 22nd, 2022, unfortunately paywalled. This reminds me of shadowy South Leinster St. There, “on the afternoon of the 10th of June 1904, James Joyce first laid eyes on his future wife Nora Barnacle as she stepped out of Finn’s Hotel where she worked as a chamber maid.” Amazed that it hadn’t become a car park during the ‘80s. You can still see its landmark sign.

Anyhow, discussing religiosity here an hour ago at our house, our “informant” (to use the correct anthropological term) mused how she identified as a cultural rather than observant Catholic. My wife then pointed to me as our interlocutor explained how she didn’t darken a sanctuary’s door, harboring hesitations given the clout of the crozier for so many centuries, but she respected the legacy all the while keeping it in check.

Vicario de Puyo confiere ministerios indígenas. En comunidad Kichwa. (2021?)

Yup. No escaping the devotion.