Chaim Grade's "Sons + Daughters": review

Between the wars: Litvaks, Vilna, Yiddishkeit without schmaltz, schtick, or fiddlers

In People Love Dead Jews, Dara Horn challenges hearers to name three Nazi death camps. Then three Yiddish authors. She critiques this titular emphasis, within and beyond the postwar Jewish community, on sentimentalizing and sensationalizing the Six Million’s fate, and far fewer survivors. Rather than celebrating and communicating the vibrancy, and the vicissitudes, of the prewar shtetls, cities and enclaves across Europe, North Africa, and Asia where Jews thrived.

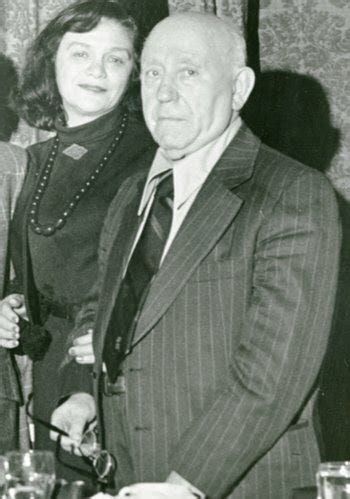

Their most acclaimed chronicler persists as Isaac Bashevis Singer (1904-1991). His elder brother Israel, already renowned for his multi-generational epics, better at them than Isaac, died in 1944. Isaac had left Warsaw in 1935, joined Israel in Manhattan, learned English, yet composed drafts of his stories, novels, children’s tales, and memoirs in Yiddish. His facility with self-promotion and self-confidence earned him the 1978’s Nobel Prize. 1986 laureate Elie Wiesel grumbled that their fellow émigré, this time to the Bronx, only after the Shoah, merited a superior claim to fame. But that rival narrator’s wife, who’d mastered English as this Yiddish refugee’s agent, nursed envy of his talent, resentful that her alleged literary gifts languished. Soviet-born, Inna Hecker dismissed Hebrew, spoke no Yiddish, yet she fronted (if not exactly backed?) his prolific career. She hated Isaac, while conniving to thwart her husband’s success.

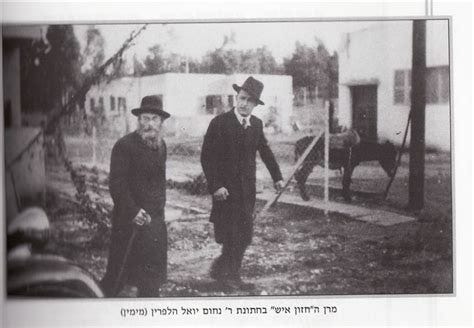

This backdrop frames our comprehension of Chaim Grade (1910-1982). Raised in Vilna, its Lithuanian, famously stern and rational schools promoted Talmudic mastery and rabbinic machers, renouncing any Polish, Kabbalah-hued, peasant-tinted, Hasidic charism. Isaac and Israel Singer both drew on the latter, the former conjuring dybbuks, angels, sorcery, and magic into folksy melodramas in vivid (and, his naysayers carped, into lurid, sexual, sexist, and sordid) scenes. Grade rejected his yeshiva training, but nonetheless found himself sharing Isaac’s exile, locked into a post-mortem evocation of glories or shames at Yiddishkeit’s height, soon twilight.

Both the Singers and Grade serialized many of their contributions in the Yiddish dailies or weeklies. As with Charles Dickens, this approach encouraged or necessitated that the portrayals of characters and the intricacy of plots hooked audiences into picking up the next issue. In Grade’s Sons and Daughters --composed in the 1960s and 1970s, but which languished due to his widow’s refusal to cooperate with publication as far back as 1982--Ruth Waldman conveys in sprightly, yet never sentimental, translation Grade’s solid skills of structuring a long-form novel which capitalizes on its mechanism of parsing out an epic and recruiting its big ensemble.

At first, a reader may quail at the lack of a roster of those roaming hundreds of pages. (An e-galley has been consulted; its print version may be handier in assistance, as there will be a glossary of Yiddish and Hebrew terms, here partially completed.) Yet Grade latches on to a device which couples his brisk chapters in succession. He multiplies his cast, if in measured cadence. He’ll mention somebody’s relative and leave it at that. Eventually, a steady storyline cycles around through the omniscient creator to concatenate such-and-such; his or her role then joins this pageant. Therefore, one isn’t overwhelmed with confusion by such profusion.

Having access only to a proof, quoting directly can’t be done. Suffice to assure, Grade’s deft touches, such as his endearing anthropomorphic attribution of emotion and chatter to leaves, clouds, bookcases, candles and buildings now and then, only enhance the depth rendered the Litvak settlements, with their muddy lanes, humid brooks, brash markets, and dimly lit small synagogues. Within unprepossessing surroundings, Grade conjures up masterful set-pieces.

Most action occurs in humdrum Morehdalye. Circa 1930, a congeries of siblings competes for their parents’ affections, denies the same, or flee abroad to a secular kibbutz, a Swiss library, or Canada. They’ll disdain or sustain their inherited commitments. As shoe-salesman, skeptic, flirt, half-wit, poet, hunchback. Zionist, socialist, Bundist, Nietzschean, or Bolshevik. None of these Jews stand as stock figures. If at a glance they risk reduction to sketchy stereotypes, according to gossipy suitors, cousins, foes, and cuckolds, they reveal themselves gutsy, sharp and rounded.

A moving encounter between a rabbi weary of Morehdalye’s in-fighting, his jaded congregants and their petty scrabble for success, with an aged, destitute counterpart surviving on his blunt faith enlightens the protagonist as to sincerity rather than sanctimony in common commitment to Torah. Grade filters this epiphany gradually and subtly. He avoids pitfalls of ginning up facile, caricatured burdens of Orthodox Judaism upon the poor. And any temptation of selling out this setting for Marxist rantsabout the oppressive system where generations scrabble in cycles of want under aristocracy dominated by Catholic nobility, now decimated by post-WWI realpolitik.

While social dynamics reverberate, they remain, as do its Gentiles generally, in the shadows. Grade shows rather than tells of the divide that, as if ordained, certainly often dictated, all but “naturally” keeps these two factions segregated in their mundane routines. There’s a boycott, catcalls, if one soccer match between goyim and Jews; throughout, foreshadowing their fate, Grade sticks to his people.

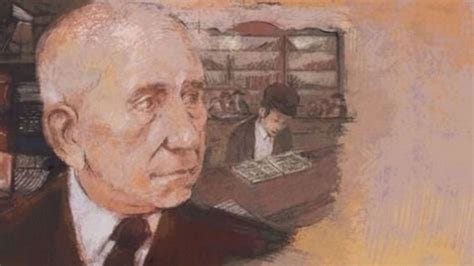

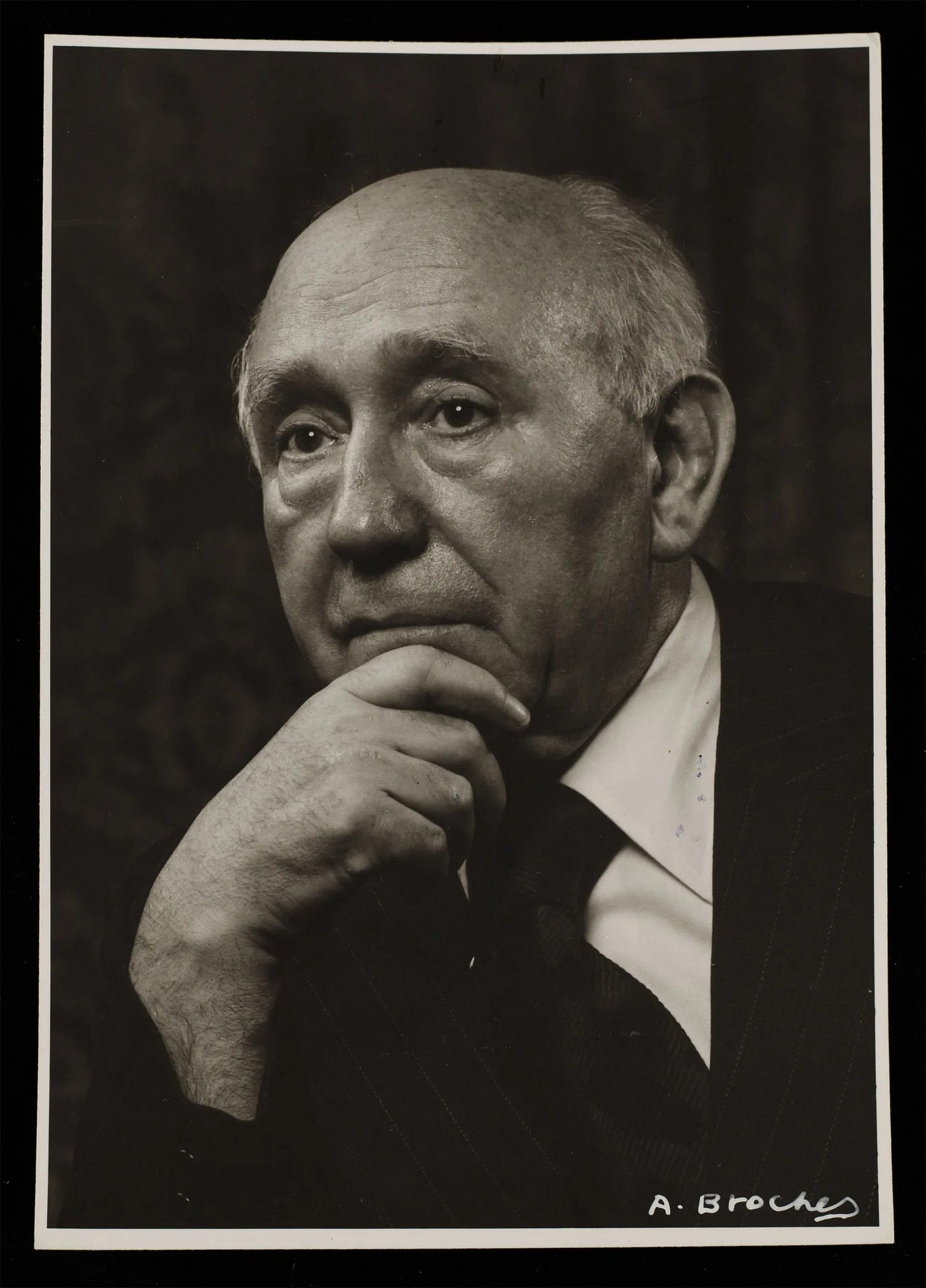

Unfortunately, this impressive volume never reached full promise. A revised manuscript had been typeset, but Grade died [his Yiddish typewriter, as he left it in 1982, above] before he could finish transforming its serial contents into a two-volume saga. For that expansive presentation of his coming-of-age, lightly fictionalized from Vilna, see The Yeshiva (1977/8), which deserves reissue. It’s to be hoped that, given Grade’s wife’s passing away in 2010, Knopf keeps offering English-language readers more from a literary legacy of an astute and canny articulator of two sides of his stark upbringing. Despite Adam Kirsch’s “quite probably the last great Yiddish novel” elegiac send-off with which he introduces Sons and Daughters, he concedes that while worldlier advocates of Yiddishkeit largely either met with premature demise or faded away, their traditional contingent, in more than one urban diaspora, speaks in a venerable mamaloshen of their savvy, sassy ancestors. Brothers Singer, with Chaim Grade, might applaud. Perhaps a future Nobel winner may emerge from those carrying on in a wry mother tongue spoken now and chiming in over a scattered millennium.

Grade early on left shul for street. Whether in or outside hallowed walls or dank cellars, his accomplishment endures. He summed himself up in a 1970 letter, as a “gravestone carver of my vanished world”. Yet, Grade engraves stolid sturdy plots elegantly, in this vivacious memorial. (Spectrum Culture 4/10/25: although The Atlantic’s critic last month echoed my conclusion, you can see from my critique on Goodreads which appeared last autumn, long before, anticipated her coda. Perhaps somebody peeked? Cf. Jewish Review of Books, The Forward, and WSJ and NYT.)

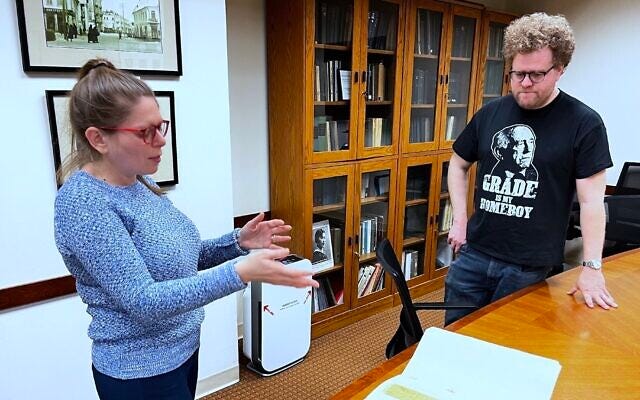

(P.S. Times of Israel interview with translator Rose Waldman. My SC entry's slightly revised, enriched with these sunny links to added insight on this recommended read.)